About Mitchell Albala

Getting the Light Right: The Power of the Color Study

(Click images throughout article for larger views)

In my studio, every painting begins with a color study. It’s a practice I adopted not long after college, when my interest in painting the color of light was in its formative stages. Now these studies are a natural part of my process. Without them, I couldn’t face of the audacious goal of translating light into paint.

I’ve never quite understood the artist who dives into a major painting without having a clear color plan. It’s true that a lot of color relationships are worked out during the course of the painting, but I have found that the clearer my color vision is at the outset, the more effective my color solution is in the final painting. The color study is a way to test that vision. The studies do take extra time and to some they may seem like an overly formal process. But I know of no better way to expand one’s color vision and flex one’s color mixing muscles than to do color studies. They are fun, practical and enormously satisfying.

As I reflect on my years of doing color studies, I can think of at least six ways they have helped my practice. After discussing each of these benefits, I’ll present examples of two different types of color studies: “Developed” and “Simple,” as well as an example of the “100 Studies” exercise I do in my workshops.

- Get the light right. Color studies are a great way to discover the color scheme that works best for a particular subject. When painting outdoors, I respond to nature. Like the Impressionists, I try trying to capture the colors as I see them. In the studio, however, I cannot respond to nature in the same way. Instead, my approach to color must be partly invented. I rely on collected memories of sunlight on certain subjects and at certain times of day. (Here, many years of observation and mixing colors outdoors pays big dividends.) I also know that it’s not possible to perfectly mimic nature’s colors, so I am willing to experiment, which is the whole point of the color study. Finding just the right combination of colors for a particular subject can take some doing. So the color study is also a practice run for the pigment choices and mixtures I’ll need. I often rely on a limited palette, just four of five colors, which helps unify the overall color in the painting. But which four or five colors I choose makes a big difference.

- Know the subject. Color studies are also a great way to familiarize yourself with the subject — not only its colors, but its patterns and shapes. You can resolve compositional issues and potentially save yourself a lot of backtracking later on.

A color study doesn’t have to be tight or very polished in order to get the message across. What are the basic color groups and how do they relate?

Deny the photo! Many landscape painters work from photographs. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this practice — if it’s done properly. Far too many artists do nothing more than copy the color they see in the photo, which circumvents the act of translating or inventing color. It becomes an uncreative color matching exercise. A series of color studies can liberate you from the limited vision proposed by the photographic color. It forces you to try alternate strategies and encourages you to be more creative with your color choices. (Also see Using Photographs Like an Artist.)

- No pressure! Psychologically, a color study is a low pressure exercise. I won’t be as invested in a small “disposable” study as I might be in a larger studio piece. (Nothing is more intimidating than a blank canvas, and the larger the canvas, the more intimidating.) The study is a safe avenue to traverse (and get lost) without a large time commitment.

- In praise of painterlyness. The smaller the study, the more painterly and gestural it is likely to be. This is easy to see in the color studies from The Way Home and Peak, below. For many artists, this is a quality that is difficult to transpose into larger pieces. An expressive study can serve as an inspiration, a gentle reminder of the touch and style you aspire to in the larger studio painting. You are more likely to stay loose and painterly (if that is your goal) if you refer to a painterly study, rather than a photo.

- Mini-masterpieces. Color studies don’t always come out well, but when they do they can be mini-masterpieces that are worthy of a place on your studio wall — or someone else’s wall. They may be entirely salable at a small works exhibit or at a studio sale.

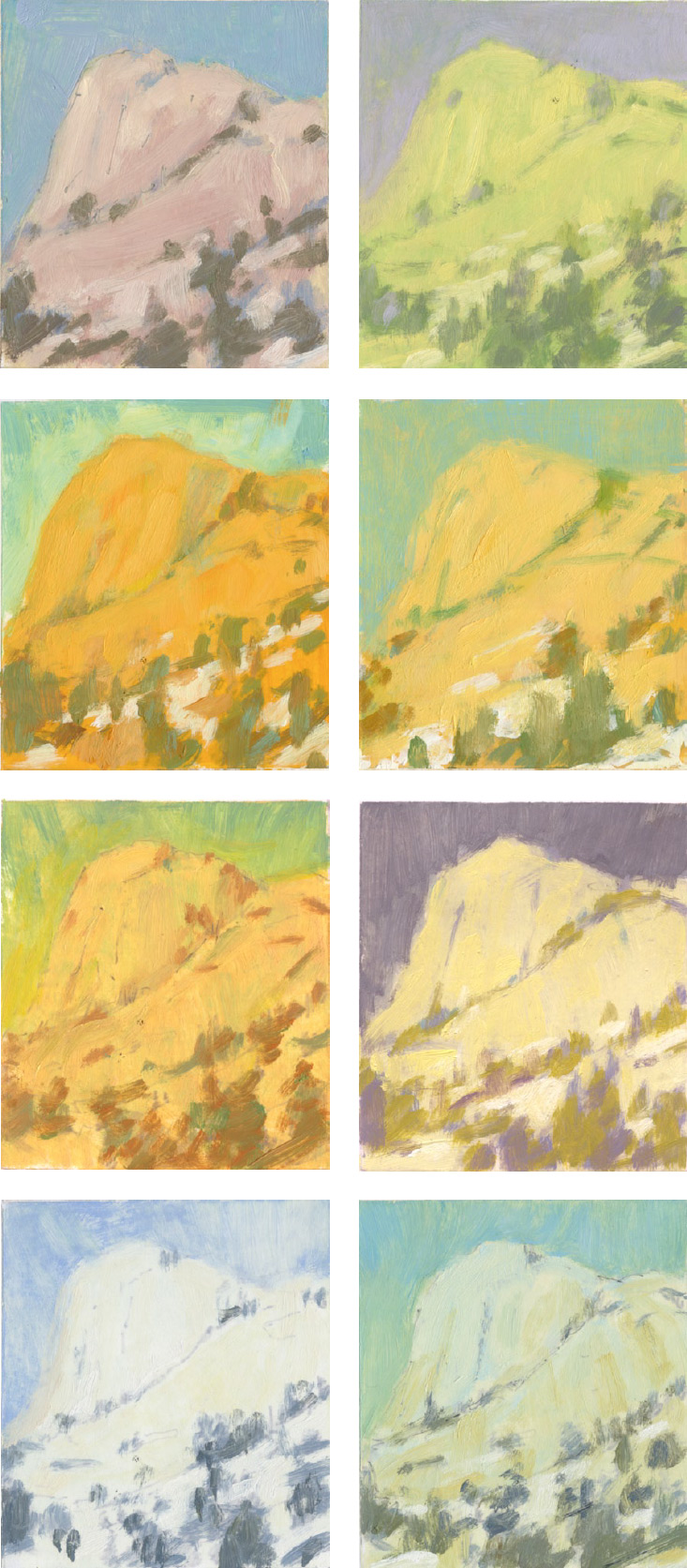

The Developed Color Study

Mitchell Albala, 2014, Color Studies, The Way Home, 8″ x 8″ each. The studies in this set are fairly developed. I took the time to consider the drawing and placement of shapes, but I also strove to keep them loose and painterly. They each took about an hour-and-a-half, about the same time I’d spend on a plein air painting. Each one makes a valid color statement, but having done them all, I have the luxury of options. I can decide which one is the best expression of my vision of the subject. I’m partial to the study in the upper right because it appears most like sunlight to me. The color strategies in these four studies, starting top left and moving clockwise: complementary (yellow-violet); analogous (yellow, yellow-green, and green) with contrasting cool accents (blue-violet); complementary (orange-blue); and analogous with contrasting temperature accents.

The Simple Color Study

Mitchell Albala, Color Studies, Peak, 4″x 3.5″ each. This set of studies, which were done for the sheer pleasure of playing with color (there was no intended final painting), are examples of what I call “simple” color studies. Unlike the developed studies (above), these only took about 15 minutes each. Because they are so small, just 4 x 3.5 inches, the brushstrokes are relatively large and gestural. How much does precision and accuracy play in this type of study? Not much. It captures only a general suggestion of shapes and no detail at all. What is important is to define the basic color groups and how they relate to each other.

“100 Studies” Exercise

Corina Linden, 2014, Color Studies, River Valley, 4? x 3? each. In my studio-based landscape workshop, Essentials of Landscape Painting, I do an exercise called “100 Studies.” Students are asked to work from a black-and-white photo and generate as many color studies as possible. So far, no one has actually done 100 studies, but they have to stretch to come up with as many ideas as they do. They try standard color strategies like complementary, analogous, split-complementary, or triadic. They try neutral strategies or turn daylight into dusk. Corina Linden says, “Color studies are a great way to experiment with color, to stretch beyond the literal and see the composition in a new way. I use them to find the color essence of the piece and work out my color strategy before I put brush to canvas.”

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

from Landscape Painting: Essential Concepts and Techniques for Plein Air and Studio Practice

Preparatory Work, page 130

from Mitchell’s blog:

Using Photographs Like an Artist

Leave a Reply