About Dennis Harper

In addition to working as an artist, Dennis Harper is Curator of Collections and Exhibitions at the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn University. Formerly Curator of Exhibitions at the Georgia Museum of Art, Harper served as curatorial advisor for Georgia for the National Museum of Women in the Arts From the States exhibition in 2003 and was a founding board member and past vice president of ATHICA: Athens Institute for Contemporary Art. Recent curatorial projects include the exhibitions As Above, So Below: Recent Works by Scherer & Ouporov; Weaving His Art on Golden Looms: Paintings and Drawings by Art Rosenbaum; and A Sinner’s Progress: The Artists Books of David Sandlin, and essays for Coming Home: American Paintings 1930–1950 from the Schoen Collection. A native of Alabama, Harper has held previous positions at Wildenstein and Co., New York, and the Visual Arts Gallery of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Harper’s own art has been exhibited across the United States and in Europe, and discussed or reproduced in American Artist, Art New England, Art Papers, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, New American Paintings, New York Times, Oxford American, and Philadelphia Inquirer, among other publications. Harper has taught studio classes at the University of Georgia on the Athens campus and in Cortona, Italy, and led workshops on egg tempera painting, fresco, and gilding.

Follow this link to visit the Artist’s Website

Egg Tempera Painting Demonstration by Dennis Harper

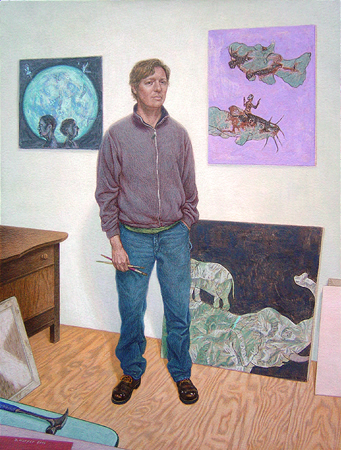

Jeffrey Whittle in His Studio – Dennis Harper“Jeffrey Whittle in His Studio” is a recent work in a series of portraits of artists in their workplaces. It is executed in straight egg yolk tempera over casein underpainting on a commercially prepared panel. The board is a vintage gesso/masonite panel, ca. 1940-50. (I bought a number of these panels from an artist’s estate.) The gesso priming is sprayed on and mottled like a rough, cold-press watercolor paper. I gotta admit, it’s a bit of a challenge for small detailed work.

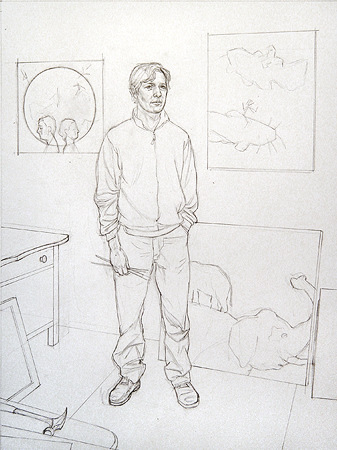

I basically follow traditional procedures as described by Cennini or Thompson. I start with a drawing the same size as my panel, from which I prepare a cartoon. I don’t normally get too involved with values or many details in the initial drawing; rather, I want to establish the composition and get gestures and proportions right.

The photo below shows the traced contours of my drawing, on sheets of vellum (patched together with drafting dots of blue tape). The orange color that bloats the lines is sanguine chalk rubbed on the reverse for transfer.

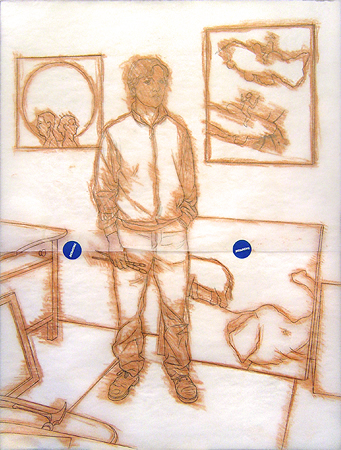

Here is the image as transferred to my panel. You can make out the faint red chalk lines and a few areas where I have begun to strengthen the transfer with a brush and dilute black casein.

I try to work up a fairly complete underpainting in monochromatic casein. I prefer it to India ink because of its particular working qualities. Casein is a little more viscous than ink, which gives me better control when thinned. I find it to be more easily reworked than ink, as well, so it’s easier for me to correct my mistakes. It leaves a very matte and absorbent surface that accepts egg tempera readily. Perhaps there may be disadvantages to casein of which I’m unaware, but I do know that Peter Hurd and many American artists in the 1940s and 50s used it for their underpainting work.

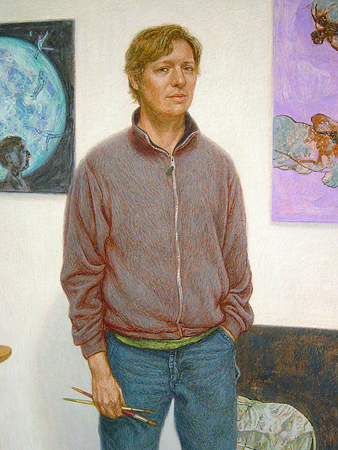

Often, I lay a wash of Venetian red (or some other warm tone) over my black underpainting to establish a middle value. This photo, in fact, shows that step along with further applications of white casein to bring back lights, as well as more black casein to continue to model the forms.

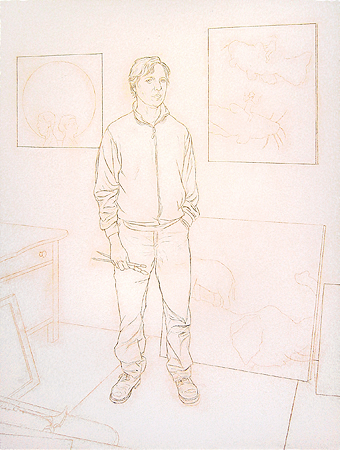

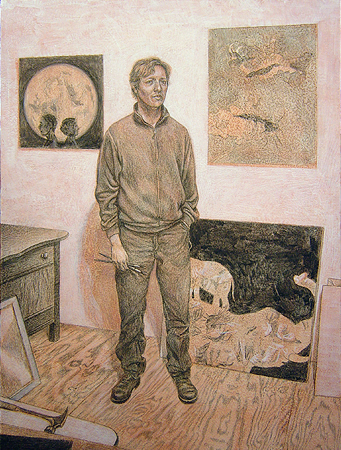

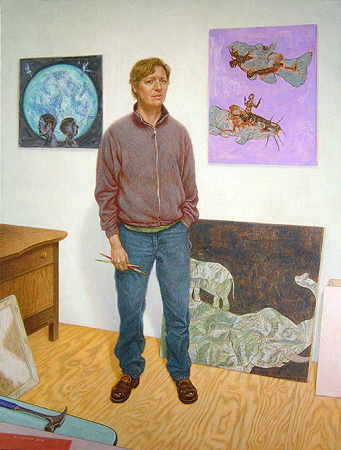

I usually take the underpainting as far as I can — that is, until I’m satisfied with the foundation or, more likely, until I grow impatient for color. This photo shows the first thin glazes of transparent local colors, now in egg tempera, with a little more deliberate color rendering on the “paintings” hanging on the wall behind him. I believe there is also a couple of washes of green earth on his head and hands by this point.

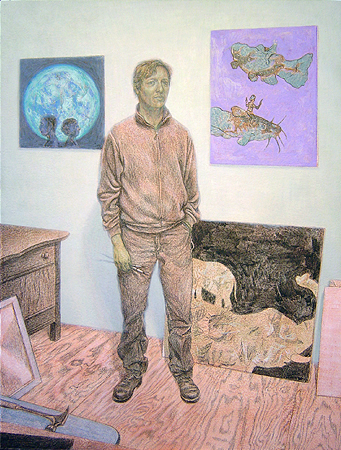

More transparent, or translucent, color washes. I still want the underpainting to show through strongly at this stage. Subsequent paint layers will become more opaque and more intense as the elements emerge from the space. Notice the caput mortuum pigment I’ve used across the subject’s jacket to provide a vibrant contrast to the gray colors that will come over it.

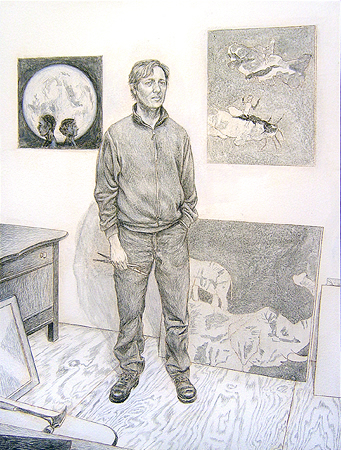

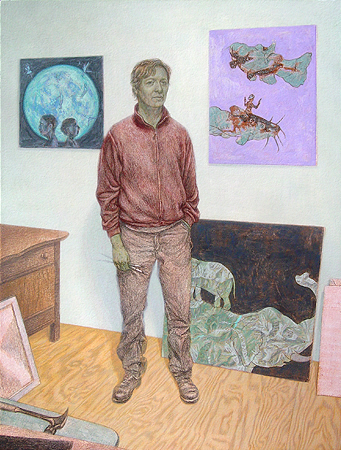

So now it’s simply time to lay in the proper colors of jeans, shirt, jacket, etc. I work mostly from back to front in the rendered space, so that nearer objects come on top of those things behind them. That probably sounds a little simple-minded, or obvious, but it really does help to depict a more believable space.

This photo actually skips forward several sessions, for brevity’s sake. After establishing all the basic local colors across the painting, I spent a good bit of time refining their interrelationships.

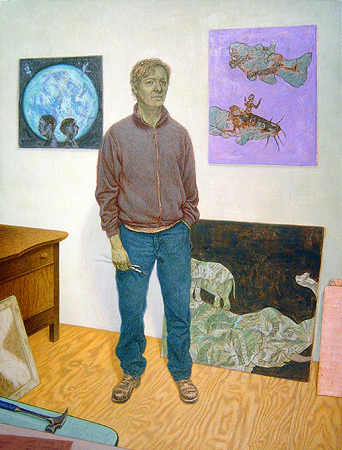

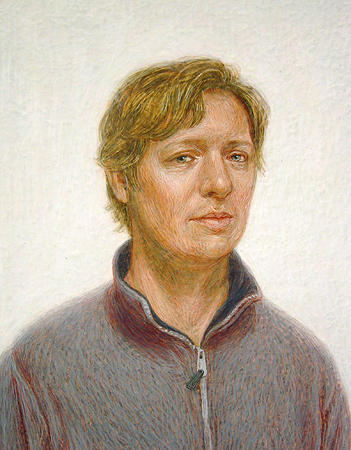

The finished painting (photographed in warmer light.) The final few painting sessions consisted of a lot of looking at the work, interrupted by minor, but crucial corrections. I adjusted probably every feature on Whittle’s face, at least a couple of times. I paid close attention to how edges met or forms overlapped. And I made slight temperature or value adjustments to some of the colors with additional glazes or hatch marks.

This first detail illustrates a little better the type of surface I strive for. I enjoy modeling the painting’s volumes with visible brush strokes that ride across planes in a kind of cross-contour map. However, I find myself constantly alternating between making distinct hatch marks and laying on broad, smooth washes or glazes.

Another detail of the finished work. I generally work from darker colors to lighter ones, from transparent mixtures to more opaque. That’s probably apparent in this view of the face where ever lighter shades of “fleshtone” build toward the strongest highlights. You can still make out the earlier-applied green earth (strengthened with verdaccio) in the shadows of his face and hair. Also you can get a hint of the dimpled texture of the gesso ground, especially in the mostly unmodulated expanse of wall behind the figure.The actual painting is 21 x 16 inches, completed 2006.

Leave a Reply